Source: PlanPhilly

Byline: Ryan Briggs, Aaron Moselle

Date: 11/11/2021

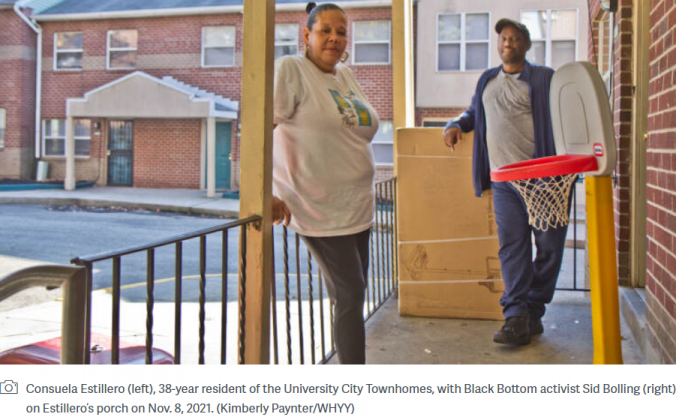

Consuela Estillero gets teary when she talks about leaving her apartment at the University City Townhomes.

Not because she’s spent nearly 40 years of her life at the affordable housing complex in West Philadelphia, and not because she raised her two kids here, who now have grandchildren she frequently visits. Those facts certainly make the impending move harder to swallow, but Estillero gets emotional because she’s genuinely worried about finding another landlord who will accept the rental voucher coming her way, a necessity precipitated by the property owner’s decision this summer not to renew a long-running contract with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Everyone at the 70-unit complex has to be out by next July.

“I know people with vouchers who can’t find a place now,” Estillero said recently from the large sectional inside her living room.

Similar agreements between property owners like Estillero’s landlord, Altman Management Company, and government agencies like HUD underpin upwards of 34,000 affordable housing units across Philadelphia, according to the National Housing Preservation Database. That more than eclipses the 12,894 units of traditional public housing at the Philadelphia Housing Authority’s projects or scattered site homes. But unlike publicly owned housing, federally assisted units like University City Townhomes rely on property owners tapping a variety of rental subsidies or tax credit deals in exchange for agreeing to restrictions that preserve developments as affordable housing for a set period of time — and at Estillero’s building, time has run out.

Vouchers and tax-credit housing have increasingly supplanted public housing nationally. But while these arrangements often last for decades, many thousands of units have also seen their affordability restriction expire over the years. Some have been redeveloped or taken market rate. In Philadelphia, 1,700 units are tied to affordability restrictions that could expire over the next five years, and 3,400 over the next decade — some have already run through their initial terms and are being reupped essentially at the will of their respective owners. In all, more than 10% of all the federally assisted housing units in the city are potentially at risk.

And while developers are creating new units under the same programs, experts say they’re not signing on fast enough to replace the losses — let alone the attrition of non-subsidized units rented by private landlords on the cheap. Observers see a slow-moving storm set to destabilize a housing market that is already strained by unmet demand for decent, affordable options.

“I think it’s very serious,” said Greg Heller, a director at management consulting firm Guidehouse and a former head of the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, which has underwritten many affordable apartment developments. “This is definitely a threat to affordable housing. Not just in Philly, but nationwide.

Displacement looms for tenants

In July, Brett Altman, principal at IBID Limited Partnership, told HUD that his company would not be renewing its affordable housing contract at University City Townhomes — for the first time in nearly 40 years.

For residents and their University City neighbors, the news came as a big blow.

Built in 1983, the block-long complex on Market Street was constructed with the explicit goal of providing affordable housing in a section of West Philadelphia reshaped by racist urban renewal practices. Known as the Black Bottom, the city demolished hundreds of neighborhood homes there in the late 1960s and early 1970s to make way for more campus space and a science and technology hub — what today is known as the University City Science Center.

Now the site, located in the same swiftly gentrifying neighborhood that the University of Pennsylvania and fast-expanding Drexel University call home, could be redeveloped with no obligation to build any affordable housing, while displacing dozens of working-class Black residents. So far, the valuable site has drawn interest from real estate companies that focus on developing lab and manufacturing space for life sciences companies, according to the Philadelphia Business Journal.

Through a spokesperson, IBID declined to comment on the sale, although Altman has said he is interested in finding a buyer that wants to develop a project that includes a low-income housing component.

But the prospect of displacement generated a public outcry.

“Eradicating affordable housing on this site would be grave injustice. Not just for the families that live here now, not just for the thousands of Black Bottom residents who were removed from this land once before, but for the future of this being a place where working-class people can afford to live in an amenity-rich neighborhood,” said City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier during a news conference held in front the complex last month.

Like her neighbors at University City Townhomes, Estillero would be able to move along with her housing voucher, which requires her to pay only 30% of her monthly income, with HUD covering the rest. But she also has poor credit, as well as an open eviction case as a result of criminal allegations filed against her son. The combination will make her even less appealing to potential landlords, who have a history of being resistant to taking on Section 8 tenants — a serious concern for someone whose income is tied to her monthly social security disability check.

She hopes she can remain in Philadelphia, her hometown, nonetheless.

“It’s just like this is a part of me,” said Estillero.

Her plight is one that will become more common nationally. Some 312,000 units of affordable housing are at risk of expiring over the next five years across the U.S. — or about 6% of all federally assisted housing units — according to the same report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition and the Public and Affordable Housing Research Corporation.

But in Northeastern cities like Philadelphia, these units make up a larger share of overall rental stock than in any other region. Here, as much as 12% of all rental housing is tied to affordability restrictions that will eventually expire — once that happens, the developments can be leased at market rates, sold, or redeveloped.

While owners can voluntarily agree to maintain affordability provisions — and some new units of affordable housing are built each year — housing policy experts, like Heller, say the city already faces a dire shortage of subsidized housing. Worse, the expiring developments also tend to be older and many are in areas that have gentrified in the decades since their construction, making their loss especially significant for cities seeking to reduce housing inequities.

“I think that’s why, when those projects are vulnerable, it becomes such a big deal,” Heller said. “Because, one, you’re losing the units, and we have a shortage of affordable units in the first place. And, two, you’re losing units in great locations.”

About eight years ago, another 84-unit affordable complex about a block away from University City Townhomes, known as Center Post Village, was acquired by Iron Stone Real Estate Partners for $8 million. Jason Friedland, director of investments for the for-profit real estate company, said it purchased Center Post along with several other federally assisted affordable housing complexes from struggling nonprofit operators around that time.

“They were older conversions into affordable housing, and this nonprofit was having a real hard time managing them. It was losing unbelievable amounts of money on them,” Friedland said. “We took over four properties and invested a lot of money in them, and continued to run them as affordable housing.”

Nearly all the complexes Iron Stone acquired are located in or near gentrifying areas: the Sartain School Apartments in Brewerytown, the Landreth Apartments in Point Breeze, and the Dunlap Apartments in West Philadelphia. Most, like Center Post, have lost their affordability restrictions or are close to it.

The townhouse-style apartment complex was constructed a decade prior to University City Townhomes and both are linked to project-based Section 8 vouchers. In 2019, the HUD agreement expired, but Iron Stone chose to voluntarily renew the arrangement on a five-year basis.

But Center Post and the other affordable complexes are outliers in Iron Stone’s portfolio. The company has amassed a large portfolio of market rate housing and life science-related properties, the latter of which Friedland says makes up the majority of their business today. Iron Stone notably purchased the former Hahnemann Hospital building for $36 million, with plans to refit the building as lab space.

Friedland said the company was not speculating on expiring affordable housing developments and had no plans to convert properties like Center Post Village, which now sits amid an increasingly valuable life science hub and will be up for a HUD renewal again in 2024. He said the guaranteed income streams associated with project-based vouchers was a key part of the company’s long-term strategy and that the company had “no incentive” to move away from affordable housing.

“Just like if you were investing in the stock market, you have a variety of investments. You don’t go all in on an emerging market,” he said. “So, we have a very diversified portfolio of real estate in Philadelphia, which has served us well. I’ve been through three recessions… So, we have market rate housing, and the market rate housing could get crushed, but we still have our affordable housing.”

Mary Smitherman, a tenant in another Iron Stone-owned affordable housing complex, hopes that remains the case. She’s lived at the Landreth Apartments, a converted school building at South 23rd and Federal streets, for the last 12 years and has no interest in moving. The 78-year-old says she didn’t feel safe at her last rental in North Philadelphia, but feels comfortable in this pocket of Point Breeze, a gentrifying area where the average one-bedroom apartment rents for $1,445, according to Apartments.com.

“Right in this little nook, we’re good,” said Smitherman, who was busy on a recent weekday setting up a sidewalk food giveaway with some of her neighbors.

Iron Stone picked up the four-story, brick building about a decade ago, and leases units at below market rate rents per the terms of a mortgage covenant with the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, which helped finance the conversion in the early 1990s. Smitherman’s one-bedroom is further subsidized by a HUD rental voucher, allowing her to pay just 30% of her income, which largely consists of her monthly social security check.

While Friedland said Iron Stone has no plans to vacate its affordability covenant, Carolyn Placke, a senior housing program officer with the community development nonprofit LISC, said many other for-profit landlords do sell once they are legally able to do so.

And, as the value of said properties increases, so does the incentive to sell.

“If you’re a mission-based, affordable housing nonprofit, the likelihood … that you’re going to move your properties to market is very slim,” she said. “But in instances where you have a private affordable housing developer, they may decide that ‘hey, this has been fantastic’ but they simply do not want to continue in the program. And that’s where the real threat is.”

Inequity grows as units are lost

Every year, some expiring units are effectively replaced by new units built by developers with fresh interest in these same housing programs. But replacing lost housing can be made more difficult as land becomes more expensive, or political dynamics change.

Locational data shows, in practice, federally assisted housing tracks strongly along racial and economic lines, skewing away from wealthy areas with high land values and a larger proportion of white residents. That trend is true in parts of North Philadelphia, where the majority-Black 19121 ZIP code hosts 4,200 units of federally-assisted housing — more than five times the number reported in the majority-white 19130 ZIP code immediately to the south, according to NHPD statistics.

Meanwhile, the ZIP code encompassing affluent downtown areas like Old City and Society Hill, contains just 59 federally assisted units. Chestnut Hill, a wealthy neighborhood on the edge of the city, and Bridesburg, a highway-bound enclave that is 90% white, both have zero units.

Heller noted the same trends that helped drive past disparities also make it more difficult to replace units in areas that have since gentrified — the same neighborhoods that could most benefit from affordable housing.

“People, and especially nonprofits, can’t just buy up multi-million dollar properties to build more affordable housing,” Heller said.

Mayor Jim Kenney ran for office with a campaign that promised to reduce racial inequities and prioritize affordable housing. Yet while work is moving ahead on efforts to create 400 new federally assisted units and preserve another 700, city spokesperson Jamila Davis said the problem extends beyond the scope of city government alone and requires federal, state, and private support.

“The City of Philadelphia has been working on solutions to address this concern,” Davis said. “The need is tremendous and requires a broad range of programs, strategies, and resources.”

And there are other solutions, in theory. Heller pointed to a provision in the Biden administration’s Build Back Better plan that would top up funding for housing vouchers — although this amount has already been slashed in congressional negotiations. Placke said other cities allow nonprofits to have right of first refusal at buying federally assisted developments that are put up for sale. Philadelphia considered a similar provision in an earlier housing bill, but ultimately rejected the idea.

Meanwhile, in West Philadelphia, Gauthier has moved forward with a strategy that aims to stop demolition at the site and keep affordable housing at the site. A bill to that effect is now making its way through City Council, though it’s unclear if the measure is enforceable.

But others noted that the sunset provisions in these affordable housing weren’t a bug. They were included as an inducement to developers, as U.S. housing policy moved away from constructing more public housing and toward more public-private partnerships.

Freidland, from Iron Stone, said that adding more restrictions to prevent the dissolution of decades-long affordable housing agreements would make it less likely developers would use these programs in the first place.

“It’s an unbelievable amount of time you’re taking land and tying it up,” he said. “The bonus they get for keeping it affordable for half a century is that they eventually get to sell it at market rate.”